Untyped lambda calculus is powerful. In fact, every computable function can be encoded into lambda calculus, and thus so can every bit of Scala code you've ever written. Though, anything more complicated than your basic combinator would be almost indecipherable in its lambda calculus form. As an example, here's what the addition combinator for the Church numerals c_n = λfx.fn(x) looks like in lambda calculus:

A+ = λxypq.xp(ypq)

At first glance it's by no means obvious that you're looking at a way to add natural numbers.

Introductory Definitions:

Before we jump into some more examples, let's step back a minute so I can provide a quick and basic introduction to untyped lambda calculus. The rules are easily accessible, and given that lambda calculus is Turing complete, their simplicity astounds me. (As a side note, because cellular automata are really cool, Conway's Game of Life is another easily definable Turing complete system.)

Now, as promised, the introduction: We define the set 𝚲 inductively as follows. Let V be a set of variables v', v'', etc.

(i) If x ∈ V, then x ∈ 𝚲.

(ii) If M,N ∈ 𝚲, then MN ∈ 𝚲.

(iii) If x ∈ V and M ∈ 𝚲, then λx.M ∈ 𝚲.

In (ii), MN denotes application, and you should think of M as a method applied to N. In (iii), the syntax λx.M denotes an abstraction, i.e. a function x -> M, where M is not required to depend on x. The most interesting terms in lambda calculus will include an abstraction followed by an application, like so:

(λx.M)N = M[x := N]

where N is substituted for every free instance of x in M. This is known formally as β-reduction. In psuedo lambda calculus, (psuedo because integers are not terms in V), we can consider the example

(λx.(2*x + 3))4 = 2*4 + 3 = 11

Some Intuitions:

So what's the benefit of thinking about lambda calculus? For me, lambda calculus provides the structure to represent the core of what a function really is: a rule that gets us from one bit of knowledge to another. And if we want to prove something about functions (functions in a generic sense), lambda calculus is the perfect place to come. So what should we prove? Well, intuitively we'd hope that, no matter the strategy (e.g. call by name, call by value, etc.) we use to evaluate our function, we obtain the same result. But wait! Can this always be true? What if our function is an ill-thought-out recursion that loops until we overflow the stack? Can we really guarantee that every call to a function will return a unique result, no matter what strategy we use to evaluate it? The answer is yes, with an added assumption.

To understand what this assumption should be, consider the famous Ω-combinator:

Ω = (λx.xx)(λx.xx)

Furthermore consider the lambda term (λx.z)Ω. If we evaluate this term using a call-by-name strategy, then it's simply equal to the constant z, since λx.z is a constant function. But if we use a call-by-value strategy, then we'll never be able to further reduce it, since when we apply λx.xx to itself we again obtain Ω. So what we really want to prove is this: If we β-reduce a lambda term until we cannot reduce it any further, then that final reduced term is unique. Said more formally: If a lambda term has a normal form, then that normal form is unique.

Introduction to Church-Rosser:

In summary, we cannot just pick an evaluation strategy and expect it to yield the same results as all other evaluation strategies, because, as the

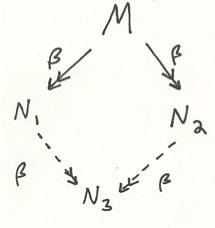

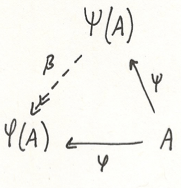

In summary, we cannot just pick an evaluation strategy and expect it to yield the same results as all other evaluation strategies, because, as the Ω-combinator example showed us, a given evaluation strategy may never terminate. But, there is something we can prove for certain: a lambda term has at most one normal form. In order to prove this, we'll outline the proof of a more general theorem, known as the Church-Rosser Theorem. In picture form, it looks like the image to the right, where solid arrows are assumptions and dotted arrows are to be proven.

In word form it states: If a term M β-reduces to two terms N1 and N2, then there exists some N3 such that N1 and N2 each β-reduce to it.

Given Church-Rosser, our desired statement follows directly. If we let N1 and N2 in the diagram above be distinct normal forms of M, then by Church-Rosser there exists some N3 such that N1 and N2 each β-reduce to it. But a normal form term can only β-reduce to itself, and thus N1 = L and N2 = L. Thus M has at most one normal form, since N1 = N2.

Interestingly, we can also use Church-Rosser to prove the consistency of lambda calculus, that is, that true does not equal false. We define:

T = λxy.x

F = λxy.y

Note that T and F are written as an iterated abstraction, meaning that the abstraction is one of multiple variables (in this case x and y). Iterated abstraction is right associative; for example

λxyz.xyz

is shorthand for

λx.(λy.(λz.xyz))

Now to understand these definitions, if K is a lambda term that equals either T or F, the lambda term KPQ is a way to represent “if K then P else Q”. If T = F, then we’d be able to perform a series of reductions connecting T and F. But since T and F are both normal forms, we cannot perform such reductions. Thus T does not equal F.

Strip Lemma Basics:

Now in order to prove Church-Rosser, we'll prove a lemma first, namely the Strip Lemma. This lemma states that, if

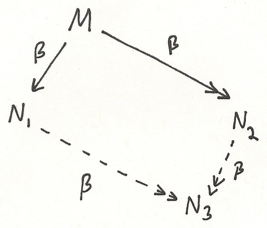

Now in order to prove Church-Rosser, we'll prove a lemma first, namely the Strip Lemma. This lemma states that, if M β-reduces to N1 in a single step, and M β-reduces to N2 in any finite number of steps, there exists an N3 such that N1 and N2 each β-reduce to it. In diagram form, we have the diagram to the right, where a single arrow represents a single β-reduction, and a double arrow represents any finite number of β-reductions.

Note that once we've proven the Strip Lemma, Church-Rosser follows immediately by induction on the natural numbers. (First prove the statement for n=1. Then prove that if the statement holds for an arbitrary n, it holds for n+1.) To see this visually, imagine filling in the Church-Rosser diagram with these strips.

Proceeding with the proof of the Strip Lemma, the correct question to ask is, how do we obtain a candidate N3? Well, we know that M β-reduces to N1 in a single step, so we'll consider this redex and mark it in M. Now as we perform the multiple reductions on M that ultimately reduce to N2, we track this marked lambda term until we reach N2. We now perform the β-reduction on this marked term in N2, and that produces our candidate N3.

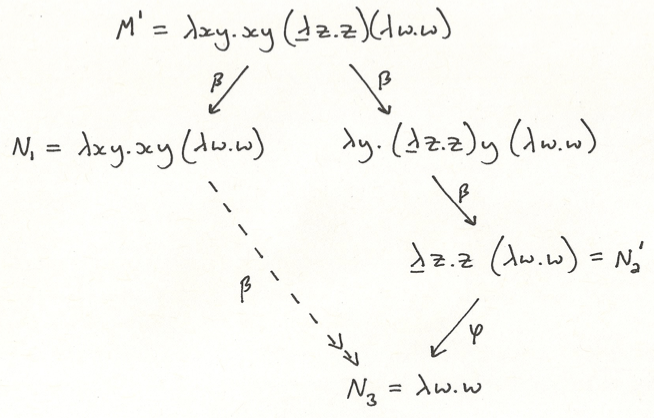

Let's make this idea of marking more formal with some notation. Specifically, to keep track of a certain redex, we'll underline it like this: (λx.M)N, and we'll keep that lambda underlined until we β-reduce it. With this new notation, here’s an example of the Strip Lemma with actual lambda terms. (We’ll introduce φ in a couple of paragraphs; for now just think of it as a β-reduction.)

Details of the Proof:

Given that we now allow underlined lambdas in our set of allowed terms, what does this new set look like formally? Let's call it 𝚲. We'll define it inductively, as we defined 𝚲 earlier. The first three parts of the definition will be analogous to before, defining variables, application, and abstraction. In the fourth part we will include underlined lambdas only in the case when we have an abstraction followed by an application. This is because the only lambda-terms we need to trace are ones we know will be β-reduced.

(i) If x ∈ V, then x ∈ 𝚲.

(ii) If M,N ∈ 𝚲, then MN ∈ 𝚲.

(iii) If x ∈ V and M ∈ 𝚲, then λx.M ∈ 𝚲.

(iv) If x ∈ V and M, N ∈ 𝚲, then (λx.M)N ∈ 𝚲.

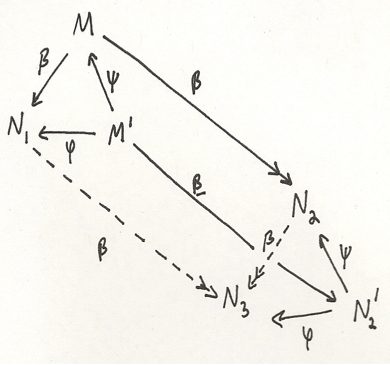

Consider the following diagram. Note that the front rectangle is the same as the diagram in the statement of the Strip Lemma. The other terms, namely M' and N2', we construct for purposes of the proof.

We construct M' to be equivalent to M, except that in it we underlined the λ that was reduced to obtain N1. The function ψ: 𝚲 -> 𝚲 simply erases all underlines, so that

ψ((λx.M)N) = (λx.ψ(M))ψ(N)We can now apply beta-reductions to M', analogous to those applied to M, in order to obtain N2'. And now to formally obtain N3, we apply the function φ: 𝚲 -> 𝚲 to N2'. And what is φ? φ is exactly what you'd expect: a function that β-reduces all underlined terms and keeps all others the same, meaning that

φ((λx.M)N) = φ(M)[x := φ(N)]Now that we have our candidate N3, we only need to prove that we can draw solid lines in place of the dotted ones. I will outline a proof showing that N2 β-reduces to N3 and will leave the other part of the proof as an exercise for the reader. We will outline a proof of the following diagram, which is the front triangle in the previous diagram.

In order to prove this, we will use the method of structural induction. Recall that initially we constructed 𝚲 inductively. Thus in order to prove something general about all elements of 𝚲, we can use an induction technique that mimics the way in which we define 𝚲. This is called induction on the structure of 𝚲. Though note that in our case, A ∈ 𝚲, so we'll use induction on the structure of 𝚲.

First, the base case:

(i) Let A = x for some x ∈ V. Then ψ(x) = x and φ(x) = x. And thus since x β-reduces to x, we're done.

For the next three cases, we assume the statement holds for the individual terms in 𝚲, and prove that it holds for their application (or abstraction).

(ii) Let A = PQ for P, Q ∈ V. Assume that ψ(P) β-reduces to φ(P) and that ψ(Q) β-reduces to φ(Q). By the definitions of ψ and φ, show that ψ(PQ) β-reduces to φ(PQ).

(iii) Let A = λx.P for P ∈ V. Assume that ψ(P) β-reduces to φ(P). Using the definitions, show that ψ(λx.P) β-reduces to φ(λx.P)

(iv) Let A = (λx.P)Q for P, Q ∈ V. Assume the statement holds for P and Q. Show that ψ(A) β-reduces to φ(A).

And that's the outline of the proof of the Strip Lemma!

Conclusion:

In summary, we gave the definition for a lambda-term, considered the Ω-combinator as an example of a lambda-term without a normal form, and outlined a proof of the Church-Rosser Theorem. So what does Church-Rosser tell us? If a term has a normal form, then that normal form is unique. This means that if we evaluate a function using two different strategies, the results will be equal. Of course, this doesn't guarantee that every evaluation strategy will terminate. But one thing we know for certain: if we do obtain a result, then that result is unique.